Just last Christmas, DIY genetic testing kits have broken sales record. Ancestry, which helps users to discover their origins, had sold 14 million DNA kids just before Thanksgiving. Meanwhile, 23andMe, a personal genomics and biotechnology company which provides its users reports on their ancestry, inherited traits, and possible genetic health concerns, assembled genetic data for more than 5 million customers.

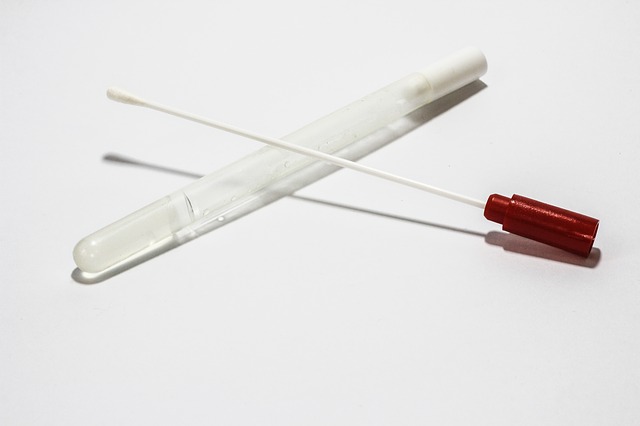

Writer Erin Brodwin issues a warning for the users of these at-home kits: these services are not at all safe, nor are they private. Consider this: when you get your DNA tested, you will be asked to provide a number of vital information. We are not only talking about your name, email, and birthdate here. You are also providing these companies a full blueprint of your life, complete with the very code that makes you unique – your DNA. The worst part of this is that your information is not truly private, it can be accessed by law enforcement with a subpoena, and if you read the fine print, it is also shared with “third parties”. In the case of 23andMe, one of those third parties is pharmaceutical giant GlaxoSmithKline.

Aside from the privacy issue, there is also the concern for the reliability of these tests. For example, one might mistakenly rejoice for not having the cancer gene, but the reality is that 23andMe does not look at your entire DNA. It only looks at parts of your code, compares it to strings that are known to be causes of cancer, and if there is nothing that match, you get a green signal for health. But experts are only beginning to understand genetics. There is so much more in the human gene, particularly those related to health, that remains a mystery.

Implications for AI

The increase in the number of people getting their genes traced and tested can be seen in a new light. We see it as the increasing desire of people to know themselves. And because science points to DNA as the determinant of everything we are as an individual, people think that by having their DNA mapped, they would be able to trace their history, and in the process, discover their purpose for existing.

Here we clearly see how materialistic science is deeply embedded in our psyche. What people fail to realize is that their current DNA is no more than an expression of the past. It tells us what we have inherited from our families, but through the science of epigenetics, we know that there are ways to alter how the DNA works. We are not a complete copy of our parents, we have the capacity to change who we are. And since epigenetic changes happen in the course of an individual’s lifetime, one might not immediately see the impacts. But our children will. And if we teach them that they are not the product of their DNA, if they realize this truth early enough, they might be able to make changes in their own lives early enough for them to reap its benefits.

Another important aspect we wish to raise here is the fact that genomics has not yet discovered the rate at which a disease can be inherited and manifested. And with transhumanists hard at work in researching life-extension methods, such mystery cannot be tolerated. As with previous mysteries, the problem has something to do with the lack of data. While we know the 23 base pairs that make up the human DNA, we do not know yet the different patterns they are arranged in different human beings, and how such arrangements are manifested in terms of disease. This is where at-home kits figure.

In the same way that we are people are offered Android phones are offered at a fraction of the price of an iPhone [see Apple’s New Product Is Privacy to understand the context of this statement], DIY DNA test kits are a hundred dollars cheaper than a DNA workup with a doctor. The reason for this is simple: you are paying, not with money, but with your own DNA data. This is but one way for movers of life-extension projects to get more data to test their theories. We know that Google is interested with DNA data (thanks to its recently ended 3-year partnership with Ancestry). Combine the AI capacity of the tech giant, and the millions of data in Ancestry’s servers and they might just solve the “missing heritability” problem.

Read Original Article

Read Online

Click the button below if you wish to read the article on the website where it was originally published.

Read Offline

Click the button below if you wish to read the original article offline.